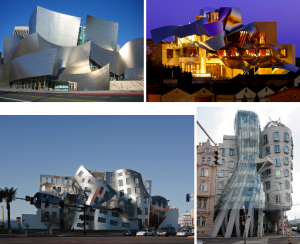

The nature of building technologies today dictate that increasing levels of complexity can be coordinated with advances in computer systems. From design to construction there exists a common platform for computationally directing the process creating our built environment. These advances labeled Building Information Modelling or BIM involves the generation and management of digital representations of physical and functional characteristics of places. BIM allows a digital “sketch” of a design to move from a basic formal model to design development, prototyping, production and installation all as data and software. In other words, with today’s BIM a common model can be used by the architectural team to design the building, the construction group to model the construction of the building and then the building owner to manage it. Throughout the process design, engineering and construction are tightly woven together in the common foundation in information provided by the computational model.

Beginning in the 2000s this common computer model brought together the architect and structural engineer and increasingly the building contractor into a new-networked computational hyper realm that was the basis for new integrated design thinking. The operation required seeing the process of building holistically yet with respect to its complexity. The development of an interoperable language that could be a basis for the sharing of common terms with architects, engineers and later builders was as important as the technical efficiencies gained by the common computational model. To sum, BIM and computational design laid the ground works to see all aspects of building — structural, material, and aesthetic — as part of a interoperable whole that was the subject of design and construction together.

In this way BIM and the parallel computational design methods between design, structure and construction it created has started to look intriguingly like the unified ideas of design and architecture that were a part of Eastern modes of building before the modern era. It is to this subject we should turn to look in depth at how an Eastern perspective can shed light in the design of architectural ceramics.

An Eastern Perspective on Making

The nature of form in art, design and architecture in the East is completely different from that of the West. Ever since the Renaissance when visual perspective, pictorial and sculptural realism became priorities in art in the West, the divergence between eastern and western modes of art became clear. In architecture and design this transformation also occurred through a neo-classicism that redirected architectural form away from material and craft towards the visual language of ancient Greco-Roman examples. Whereas Romanesque, Byzantine and Gothic architecture along with vernacular examples were focused on the union of form, materiality and decoration, neo-classicism largely separated architectural form from the physical reality of its indigenous base. Overall art and architecture became discrete and separate activities that took their meaning primarily through individual expression aligned to economy and politics. From Renaissance patrons to Baroque and Enlightenment royalty up to the 19-century imperialists and first industrialists, realist, perspectival art and the associated neoclassic architecture were at the service of the political and economic imperatives and hence cultural tastes of these groups up until to the onset of Modernism.

In Eastern cultures the division between art, architecture, design and building never occurred in this way. All types of form making in visual creative practices came out of a unitary understanding of the world that connected human expression to a larger cosmological worldview. In this way Eastern forms of making were closely aligned to functional needs tied to a mix of local material conditions based on Eastern belief systems. While the role of the individual did exist it was always as a vehicle for a larger philosophy bringing together man, nature and the universe. What the West knew as science, art, religion was up to the 19th century in the East simply the manner in which man created meaningful relations between himself and the world in material reality.

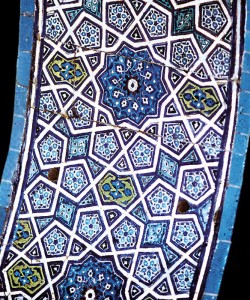

Abstraction played a key role in this process of creating profound relations between man and his environment. The application of abstract geometries and patterns tied in part to mathematics was the visual form of expression that generated works as buildings, interiors and objects that surrounded mankind. Visuality while important was much like personal vision subsumed into the greater cosmology combined with material reality. The role of the individual practitioner was to adapt local techniques to these abstract geometries.

For centuries the masters of Eastern form making relied on this method. For example, in the Turkish Ottoman Empire this unity between geometry and pattern can readily be seen in the 98-foot-long Topkapı Scroll, a compendium of 114 individual geometric patterns for wall surfaces and architecture. Used by craftsmen responsible for building in the Islamic world, the scroll illuminates the role of geometry as a primary design conceit for the area’s hybrid Eurasian culture. Up until the 20th century despite the propagation of neo-classicism and then modernism in architecture these geometric and pattern based forms of abstract composition still were important in Turkey. Especially in what we know of as craft, traditional arts such as textiles, ceramics, pottery, basket weaving, metalwork and jewelry relied on the geometric pattern in the “design” of this work. The method of composition often abstract yet tied to handcraft, technique and material remained in existence in these arts in the 21st century.

Conclusion: Architectural Ceramics in the 21st Century

Today we can start to think about how an eastern perspective to making can be related to the holistic view of construction that underlies the common computational model implied by BIM. Here the design view for architectural ceramics unites these advances in technology with tradition and modernism to point to new directions for design, engineering and construction together.

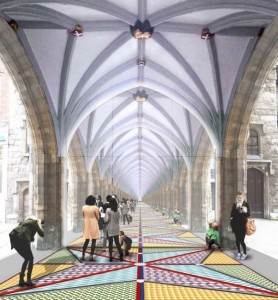

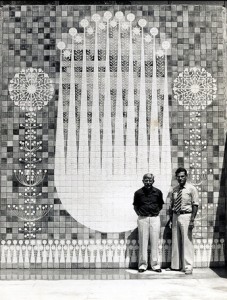

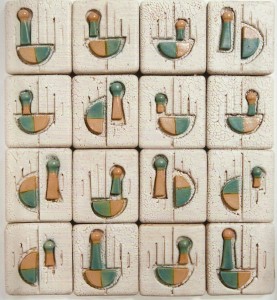

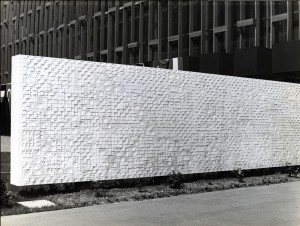

In fact it is the process in the realm of ceramics that I have tried to outline in this group of articles for the Turkish Ceramics blog. Initially in the first article, HUMANE GEOMETRIES, we looked at ways to generate new architectures from a basis in the pattern based design possibilities of materials such as ceramic dating from Medieval Islamic Architecture. Geometric patterns in surface materials and building units extending from the micro to the macro dimensions of building from these historical design/building systems provide intriguing design strategies coordinated with present needs. After looking at these ancient methods we moved into the modern period in the second article DEEP SPECIFICiTY, looking at the architectural ceramics of modernist Turkish ceramicists Belma and Sadi Diren specifically their geometric surfaces in ceramic tiles, panels and murals that complemented the space and light of modern architectural settings. Utilizing the traditions of creating abstract forms through patternmaking the Direns realigned these craft based traditions to design to a completely new modern synthesis of form and material.

And in conclusion in this article we have reviewed the possibilities of BIM and computational design and seen how its holistic view of design and building is close in spirit to the Eastern approach to making and building. We have seen that these two making cultures share the same interests in seeing the creation of the built environment in a holistic way where design, engineering and construction are closely connected.

The next step in this process is to see further advances in these holistic methods applied to architectural ceramics as we move past modernism into 21st century design. There have already been recent examples where architectural ceramics have through the aid of computational design or BIM have been integrated into a building’s overall design approach. We can point to projects such as the exterior ceramic façade of the Austrian Pavilion at Expo 2010 by Austrian architects Matias del Campo and Sandra Manninger of Span and Arkan Zeytinoğlu where the small round ceramic tiles facilitate the highly complex shape of the building. Or we can look at the Porcelain Cladding system by the designers Billings Jackson that can be used to generate a variety of formal facade alternatives. And lastly there is also a more craft and design based approach within a complex building program seen in Eric Parry’s New Bond Street Facade, London and Maria Botta’s terracotta surfaces in the Bechtler Museum of Modern Art, Charlotte, North Carolina, 2010. In all of these large-scale architectural projects architectural ceramics have played an important role in creating character and advanced design through its materiality and visual properties. These projects show that architectural ceramics have an important role to play in 21st century life.

This role though needs to be studied and applied in more depth based on the still important nature of making that we see originating out of Eastern practices. A future direction for architectural ceramics and architecture in general lies in this synthesis of computation and the eastern holistic approach to making that combines design, engineering and construction. While many other materials of course can be applied this way, architectural ceramics as the oldest of man’s building materials with its flexibility, durability and malleability show a degree of potential in creating rich and complex environments closely aligned to computational design and construction. Architectural ceramics in the 21st century as cladding, decoration and structure presents an ecological design approach for a variety of functions from facades, rainscreens and sunscreens and beyond.

But more importantly architectural ceramics as we have seen in Eastern examples of Islamic, Ottoman and Turkish architecture have the potential to formally unify a design through patterns and geometries that relate human scale to the increasingly massive scale of cities today with connections to the patterns and cycles of nature. This harmony between man, the built environment and the larger natural world through material and geometry will continue man’s ancient practice of building their world from the basic materials of the earth through ceramics.

ABOUT GÖKHAN KARAKUŞ

Gökhan Karakuş is an Istanbul-based designer, curator and writer. He is the founder and director of Emedya Design, an interactive and environmental design studio creating a range of projects including wayfinding, exhibitions and publications. As a writer he is the editor of the stone architecture magazine, Natura, and a regular contributor to leading global architecture publications such as Detail, The Architect’s Journal, Architectural Record, Dwell and Bauwelt. He is also a curator of many important exhibitions on architecture and design including the recent exhibition, The Performance of Modernity: Atatürk Kültür Merkezi, 1946-1977, on Turkey’s modern opera house at Salt Galata in Istanbul.

He is a noted lecturer on topics such as architecture in non-Western contexts, design and craft.

Twitter: @gokhankarakus

![rem-koolhaas-cctv-hoofdkwartier-beijing[1]](http://blog.turkishceramics.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/rem-koolhaas-cctv-hoofdkwartier-beijing1-300x182.jpg)